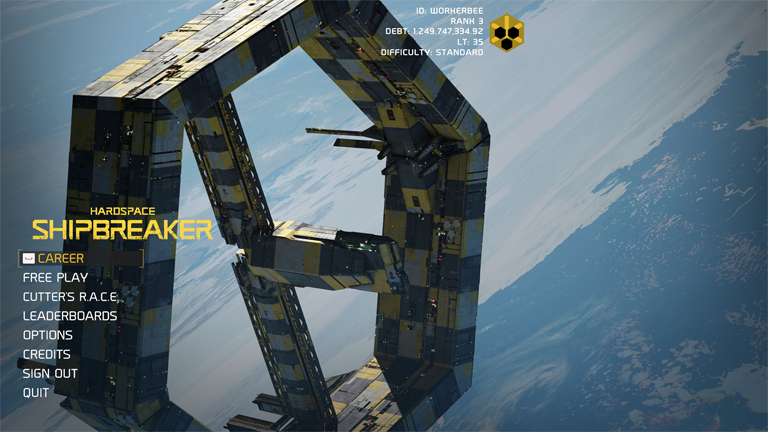

Hardspace: Shipbreaker – the 2022 zero-g puzzle by Canadian dev Blackbird Interactive – is a game of many parts. There's the core salvaging simulation, a narrative about corporate greed and worker exploitation, a competitive aspect in the form of timed trials and ranking ladders and more laid-back activities that let you collect abandoned plushies, decorate your spartan living quarters or listen to found audio logs...

Is Shipbreaker a puzzle game, then? Or a blue-collar underdog adventure? A time trial whose goal is to beat another player's best? Or a casual title that lets you collect posters and stickers?

The short answer is — yes.

The game's hodgepodge of componentry is down to the fact that Blackbird didn't go the traditional route when designing Hardspace: Shipbreaker (wherein you decide what you want to make and then take steps to make it). Rather, the studio came up with the mechanics first – for other games that didn't pan out – and then picked a concept that suited them.

To wit, the grapple mechanic came from a title about moving around procedurally generated asteroids — the cutter from an idea for a platformer. Then someone heard about the Alang Ship Breaking Yard in India ("the world's largest ship breaking yard, responsible for dismantling a significant number of retired freight and cargo ships"); and the idea for Shipbreaker finally coalesced.

The reason I mention this is the fact that – for as good as its core gameplay loop is – Hardspace: Shipbreaker feels disjointed: like a production where every individual aspect of the game was made by a different person and then crammed together... Not bad, mind – the game is very engaging and there is plenty to love here. Some aspects just feel more polished than others.

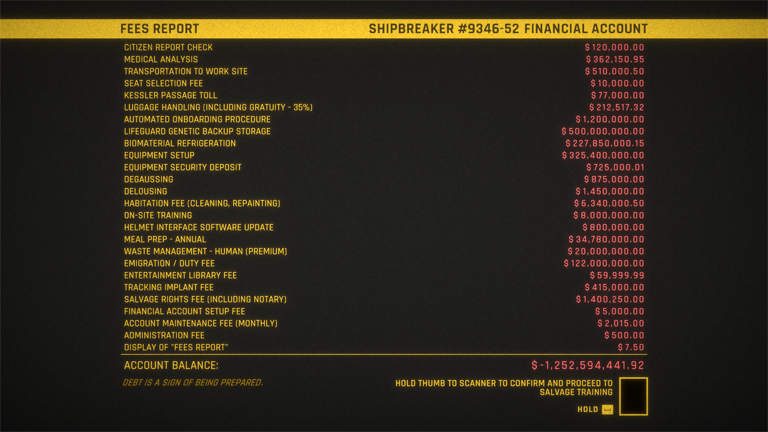

In the game, Earth has arrived at the debilitating intersection of rampant capitalism and climate change. Life is hard, work is scarce and the PC (called Shipbreaker #9346-52 – or 52, to their mates); is compelled to sign up for orbital salvage work with the Lynx corporation. As part of its truly Paranoia-worthy employment contract, the player signs away rights to 52's DNA so that a clone can continue their labor should they meet an untimely demise (which – seeing as how one of Lynx's maxims is "safety third" – is not an uncommon occurence); and, oh yeah, incurs 1.3 billion credits of debt.

Each working day, 52 wakes up, goes to their yard (each Lynx salvage yard staffs one shipbreaker); and strips a new spacecraft down to its component parts. Deposited correctly into appropriate receptacles (furnace, processor or barge), the parts earn 52 credits (from 10 for a bottle or a packet of food, to three million for a nuclear reactor that might blow up in your face as you try to remove it); which, in turn, chip away at their Olympus Mons-sized mountain of debt.

The game starts out easy (at hazard level one) with ships that are little more than hull and then gradually ramps up the difficulty (to hazard level nine) by introducing new mechanics such as fires and short-circuits, fuel lines and thrusters, reactors, pressurization, coolant, radiation and malfunctioning machinery.

To aid 52 in their work, they are equipped with a cutter, a grapple, scanner and – later – demolition charges.

The cutter can melt structural anchors or cut a straight line through hull; the grapple is used to move detached ship part about or tether them to surfaces (which pulls heavier objects in a given direction); the scanner gives you X-ray vision, so you can tell which areas of a ship are pressurized or where certain components are located; and the demo charges, as you may have guessed, blow stuff up.

The zero-g salvage yard element of Hardspace: Shipbreaker is easily its best component (well, it and one stomper of a folksy soundtrack). Navigating zero gravity and gradually solving the structural puzzle of each ship is a lot of fun (even if, occasionally, you end up getting squished by six tonnes of hull, vaporized by a reactor explosion, burnt in a flash-fire or suffocated because you cracked yourself on the helmet with a bench).

Each class of vessel comes with its own challenges and discovering a route to a crawlspace that will let you detach hull plates, successfully decoupling a Class 2 reactor or watching a door blow past you in a bout of explosive decompression all feel immensely satisfying (though some of the larger ships, which can take a few hours to take apart completely, start to feel like actual work).

The salvaging dangers are compounded by thruster fuel and oxygen (both deplete with time and use); deteriorating tool reliability (let it drop too low and tools can malfunction); and the fact that tethers are finite. Supplies have to be bought from a little kiosk and can set you back anywhere from a few thousand (for oxygen or a pack of tethers) to 150 thousand credits (for a new clone, should you croak). And while some supplies can be applied immediately (like fuel or health), repairing equipment can only be done between sessions in your hub.

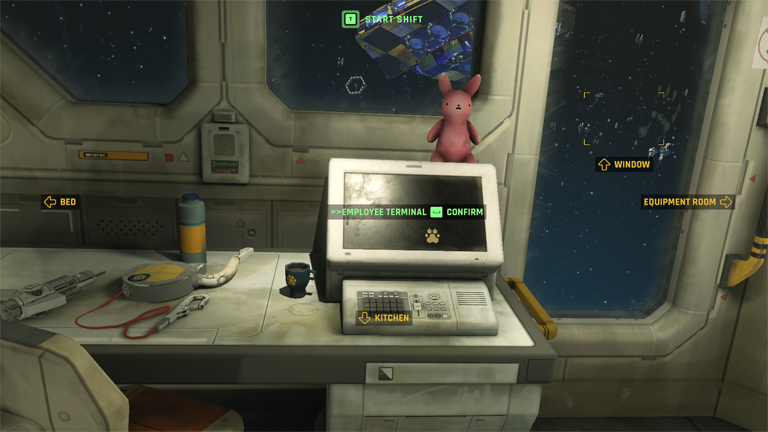

Speaking of which, the hub is where Shipbreaker starts to falter a bit. Little more than a menu that shuttles you between points of interest (you press a key and the game yanks your character to the place you selected); it's a puzzling solution in a game with such a robust 3D engine. It should have been easy to animate walking and let you explore your living space as you please... Not that having it work the way it does isn't a valid design decision, but – compared to the freedom of movement in the salvage yard – it's just jarring and feels like a half-measure.

The hub is also where you experience most of the game's narrative. I say "experience" rather than "participate in" because Shipbreaker's story, such as it is, is merely told to you via comms from your supervisor or the 'breakers working at other nearby yards. A little dry ("workers unite" and "corporations are bad" pretty much sums it up); it offers a nice enough reprieve from the salvaging and some investment into the game's Career mode but – again – feels like a tacked-on afterthought (especially when coupled with the hand-drawn character portraits which clash with the higher-quality finish of the game's 3D assets).

Lastly, the game's competitive elements (leaderboards and the Cutter's Race) clash with its central premise. It's as if, on the one trotter, the devs were decrying corporate exploitation and being forced to work far too quickly in unsafe conditions, but on the other – with a sly wink – saying "but, hey, if you want a timed race, who are we to stop you?" It might be overly critical of me to point out, but also feels disingenuous and a bit opportunistic – a compromise of vision, if you will, that reinforces the ad hoc vibe of the production...

Because the game runs on Unity (because of course it does), there is a hitch every time you perform an action for the first time in a given playthrough (as if the game suddenly realized it needed to load an animation). It's not that big a deal, but noticeable – given how smooth the game runs, otherwise.

On the whole, Hardspace: Shipbreaker is a very good game with just a few unpolished areas holding it back from being great. The core mechanic (zero-g salvaging) does perform most of the heavy lifting (pun intended), but its other aspects aren't that far behind. While a streamlined concept and a more even application of polish would have helped, it's still an easy recommendation for anyone who enjoys EVAs, spacecraft, hard science fiction or simple, honest work.

Even if its execution makes it tricky to guess just what it is trying to be or what message it wants to convey, I'm here to tell you — Hardspace: Shipbreaker is a game worth knowing.