Despite recent, rekindled interest – generated by Cyberpunk 2077 – as a genre, cyberpunk has been historically under-represented in games. If you wanted to score premium loot in a mythical dungeon, work some mud into the treads of a rally car, battle feudal space-cats among the stars or relive the highlights of the Last Crusade, plenty of options were on hand to meet your gaming needs... But the instant your interests veered more toward implants and augmentations, corporate overreach, urban combat or a bleak outlook on the future — crickets.

Oh, sure, there were a few decent cyberpunk titles to tide you over.

Adventures like Beneath a Steel Sky (1994) or Blade Runner (1997) offered glimpses of a distant, grimy tomorrow; action games like Syndicate (1993) or System Shock (1994) let you take potshots at certain aspects of The System; and the odd RPG like Shadowrun (1994) gave you slivers of choice in an uncertain reality... But each game was little more than a porthole: a wee, constrained window onto fragments of an imagined whole.

You couldn't go where you pleased in Beneath a Steel Sky, talk your way out of a Syndicate op or explore a city other than Seattle in Shadowrun (not that there's anything wrong with Seattle).

Then, in 2000, with a confident "that's enough of that" harrumph, Ion Storm Austin dropped Deus Ex onto an unsuspecting populace — and the gaming landscape would never be the same...

Deus Ex (2000): Breaking boundaries

While every game in the series is constructed around similar foundational themes (conspiracy, terrorism and a broad skepticism toward authority); the original Deus Ex (2000) was, by far, the most revolutionary. Against a stage groaning under the weight of linear experiences and limited engagement, it offered (even by today's standards) a vast game world, a dynamic plot which could be altered by player choices, complex gameplay mechanics, inspired level design and oodles of genuine freedom.

In the game, you played JC Denton – a next-generation, augmented operative working for the United Nations Anti-Terrorist Coalition. Tasked with resolving a standoff on Liberty Island, where a terrorist group called the National Secessionist Force intercepted shipments of a vital vaccine, JC's tenure as a loyal employee would turn out to be rather shortlived. In a twist the IP is known for, JC would – over the course of his adventures – have a peek behind the curtain draped over his worldview and alter his stance accordingly.

The game had (and still has) plenty going for it.

For starters, even though you were locked into playing a character called JC Denton, who he actually was was entirely up to you. You could name your character (as "JC Denton" is just the alias the character operates under); select his appearance (from five available faces, which would also affect how JC's brother – Paul – would appear in-game); and invest in 11 available skills which had a quantifiable impact on the game.

The five weapon skills, for instance, affected the size of your in-game aiming reticle and said reticle designated an area within which the game would randomly assign hits when you pulled the trigger. So if your JC was all thumbs with a pistol, the reticle would be so large, you'd have to walk the muzzle into a target to guarantee a hit.

Other skills, such as computer proficiency, environmental training or swimming, allowed you to hack certain types of machines – such as ATMs – increased the duration of consumables or gave you more oxygen underwater.

To make the most of such a varied array of skills, Deus Ex level design offered mutliple approaches to every objective and interspersed each of its 37 distinct areas (the most of any game in the franchise); with secret nooks and crannies that would reward curious JCs with additional items or much needed information (such as passwords or access codes).

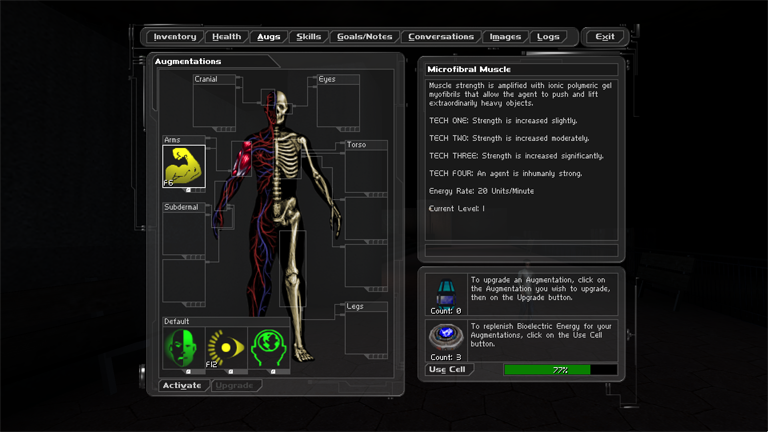

Aside from skills, JC's augmentations further varied the gameplay by overlaying a suite of implants that could be tailored to suit a particular playstyle. If your JC was of a weaselly persuasion, for instance, you could invest your Augmentation Upgrade Canisters (AUCs) into Run Silent, Cloak or Radar Transparency to make the PC more sneaky, invisible to the human eye or cameras. If, on the other trotter, you preferred something more dramatic and drastic, you could improve JC's Ballistic Protection, Regeneration and Aggressive Defense System to soak more damage, replenish lost health and detonate JC-bound projectiles in mid-air, before they could do him any harm...

All that coupled with weapon modifications (which could improve baseline stats); and consequential dialogue (which could award bonuses or even offer alternative ways to resolve any given task); made for a compelling experience that offered great player agency, rewarded curiosity and exploration and allowed actual role-playing to take place within first-person confines.

The only places where Deus Ex faltered were combat – which was shortchanged by the limited behavior of enemies, who teetered between simplistic tactics ("Armed intruder! I'm gonna run at 'em!"); and decidedly odd behavior ("Armed intruder! Time to peg it in a completely random direction!") – and the progressive erosion of the plot which, by the last act, was more reminiscent of an X-Files outtake than the game's initial, straightforward premise.

Still, for as many hurdles as Ion Storm had to overcome to produce it, Deus Ex ended up a surprisingly coherent and eminently replayable milestone for gaming in general and the cyberpunk genre in particular. Because of solid sales, numerous awards and favorable reviews, the game was all but guaranteed a sequel, which would hit the shelves three years later with all the impact of — an understuffed beanbag...

Invisible War (2003): Unfortunate streamlining

While not a bad follow-up, the second entry in the franchise was somewhat underwhelming. Why, in the wake of a game that prided itself on freedom and choice, Ion Storm decided to offer less of both can be best explained by the fact the game was a console release first and had to be trimmed down to the paltry capabilities of the Xbox.

So while the core mechanics (and appeal) of Deus Ex remained largely intact, everything was made simpler, smaller and much, much shorter (for a sequel, Invisible War only offered half the gameplay of the original game – about 18 hours' worth, all told, against Deus Ex's 39).

Other than being short, the game was also – in many respects – too distinct. By moving its setting 20 years into the future, changing the cast and the design aesthetic, Ion Storm all but ensured Invisible War would feel more like its own, disparate thing rather than the second entry of an established franchise...

Still, despite its shortcomings, Invisible War was not without its upsides.

The writing, while not outstanding, was competent, with a few quests nearing the "notable" mark (like the turf war between competing Starbucks-spoofing coffee chains); some factions were pretty neat (like the Omar – people who underwent so much augmentation as to write themselves outside the very definition of "human"); and the amount of player agency and choice – while half that of the original – was still present throughout (with some careful maneuvering, Invisible War can be completed without having to kill a single person).

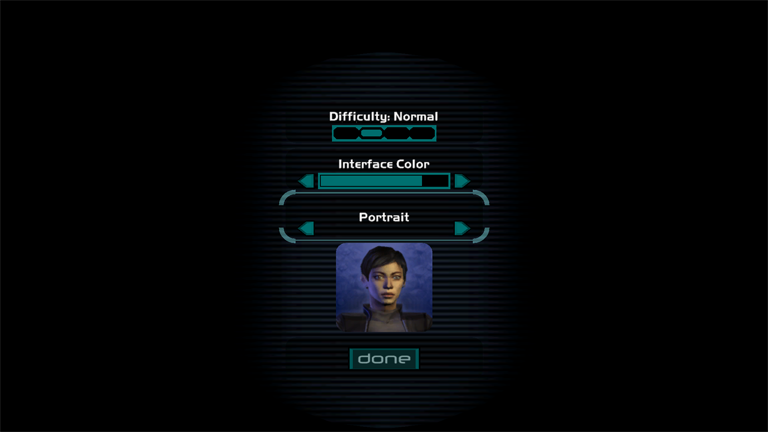

Most notably, even though the game redacted actual character creation, Invisible War is the only game in the Deus Ex IP that offers a choice of gender and the main character – Alex D – can be male or female (which does affect certain junctures of narrative, if not exactly in a significant manner).

Honestly, if Invisible War was released as a standalone game (instead of a Deus Ex sequel), I think it would be seen in a much more favorable light. There is nothing inherently wrong with it: it just had the bad luck to follow in the footsteps of what is considered one of the most groundbreaking games in the history of, uh, gaming...

Following a respectable release, Ion Storm tried to get a third game off the ground before poor finances and staff shortages saw the studio close in 2005. Eidos – the publisher and owner of Ion Storm – then passed the future of the franchise into the capable hands of newly-formed Eidos-Montreal (which, in 2007 – when development began – numbered four people).

Eidos-Montreal would spend the next four years developing the game with a fresh staff, revamped design and mechanics "inspired" (read: "borrowed from") other successful games before releasing game three (which turned out to be game minus two) in 2011.

But, like most good things in life, Deus Ex: Human Revolution turned out to be worth the wait (even if Eidos wouldn't see the fruits of its labor, bought out – as it was – by Square Enix in 2009).

Human Revolution (2011): Ghost in the machine

Before I go any further, lemme just say that any direct comparison between the two Ion Storm Deus Ex games and the two Eidos-Montreal prequels is an unfair one.

When Warren Spector and Harvey Smith set out to make the original in 2000, they had no precedent, 20 people and Unreal Engine one. They were trailblazers – responsible for creating an original world, as-yet-untested mechanics and gameplay elements that had not been tried before. While certain aspects of Deus Ex were influenced by other games (such as Half-Life or Thief); the overall result was something no-one had previously attempted.

Not so for Human Revolution.

While superior in pretty much every way, the third Deus Ex game's development was much more deliberate, better-funded and better-equipped to make for a memorable experience. With about 300 staff, no fewer than two other studios (Visual Works and Goldtooth Creative) collaborating on the project and the ability to pick and choose from tried-and-true, existing solutions to gameplay mechanics (such as the outsourced, Metal Gear Solid-like boss battles, F.E.A.R's combat algorithms or stealth from Escape from Butcher Bay); it's little wonder that – over the course of four years – Eidos-Montreal created something truly remarkable.

While nods to the original game's central themes remained (conspiracies, distrust of government and terrorism); the main focus was placed squarely on transhumanism – surpassing the limits of the human condition while trying to retain some actual humanity.

The game world was set 25 years prior to the events of Deus Ex, with cybernetic – rather than nanotechnological – implants being the cutting edge of advancement and the main character – Adam Jensen – was introduced as a "mere" flesh-and-blood security consultant who would then (over the course of the gameplay) become enhanced, with the player able to experience the emotional fallout from such a drastic change firsthand.

Unlike the Dentons, who were sorta defined but also kinda blank slates players could imprint playstyles over, Adam Jensen – in a first for the IP – had a personality, opinions and relationships. Depending on the choices you made, you could see how individual decisions affected him and listen to what he thought of them. It gave Human Revolution some much needed (or at least appreciated) emotional depth.

As for the gameplay, the game didn't veer that much from the original.

Sure, some new elements put in an appearance – such as a third-person cover camera, animated takedowns and new augmentation upgrade mechanics (using Praxis Kits in place of the old/new AUCs) – but the core experience – sandbox-y exploration, augmentations, branching plot structure and consequential dialogue – remained largely unchanged.

You still controlled the action from first-person (with a third-person view coming into play while using cover or bonking somebody on the head); you still had to track down computer passwords and access codes and any given situation could be approached in a multitude of ways.

The plot was also a lot more coherent and even-handed than either of the Ion Storm installments, with a simple, clear-cut premise (the emergence of a new, augmented breed of human and the resultant clash with the "normal" underclass majority); that lead to a grand (if somewhat rushed and simplified), logical conclusion.

Human Revolution also expanded game length back up to the 44 hour mark and increased the size and complexity of its environments to something more in line with the original game.

Because of its overwhelming financial success, Square Enix (naturally) green-lit a bunch of associated releases (such as a DLC and a mobile spin-off, which I won't comment on because — meh); as well as a direct sequel called Mankind Divided, which would (unfortunately) prove to be the last entry in the franchise when it released in 2016.

Mankind Divided (2016): Final upgrade

As is often the case (because new technology is better and nostalgia only goes so far), the last game in the Deus Ex franchise also turned out to be the best one.

Set two years after the conclusion of Human Revolution, Mankind Divided built upon established themes (the so-called "mechanical apartheid"); reined in the scale of the game world while drastically increasing its intricacy (discovering all of the secret areas in Prague is literally the most fun you can have in the game); and further refined the already solid writing for a plot that is concise, cohesive and consequential.

The game got a brand new graphics engine (Dawn replacing Human Revolution's modified Crystal Engine); algorithms were rewritten (into a system that had separate layers for combat and stealth); augmentations – streamlined – and the tone of the narrative made more complex and somber. On the whole, the prequel-sequel wasn't so much a reinvention as a thorough refinement – like flush rivets on the H-1 racer. Gameplay length also increased into the 50 hour range.

Mankind Divided garnered plenty of critical acclaim, but didn't sell all that well, which made Square Enix shift Eidos-Montreal's focus to other projects, effectively putting the future of Deus Ex on ice.

A planned sequel was cancelled in 2017 and then, in 2022, the Embracer Group got its icky, slimy, holding company tentacles over the franchise and things went downhill quickly from there...

No future

Following its acquisition by the Embracer Group, Eidos-Montreal (again) announced it was developing a new Deus Ex game in 2022, which the vile kraken axed two years later, in 2024, firing 97 employees while it was at it. A further 75 devs were fired a year later, cutting Eidos-Montreal's workforce in half.

While the studio still – technically – exists, the fact it is now owned by the same private equity mess known for its voracious appetite and questionable business sense (these are the same folks who shuttered Volition and Piranha Bytes, had no qualms accepting a 1B USD investment from Saudi Arabia, and cut its workforce by half – firing 7,828 people in 2024 – when a 2B USD deal "unexpectedly fell through"); doesn't paint the future of the franchise in a hopeful light.

Still, even though we may never see a new installment in the series, Deus Ex is an IP with no weak entries (provided you ignore – as I do – all the cash-grab flotsam produced in the wake of the actual games' success).

Whether you play the original, for its revolutionary design and mighty nostalgia factor; Invisible War for its – some might say foolhardy, some might say brave – departure from canon so it could Be Its Own Thing; Human Revolution for its coherence and empathy, or Mankind Divided for the ultimate coalescence and refinement of everything that came before — there are no wrong choices here. Every game has plenty of fun on tap and stands firm on its own merits.

So if you crave some cyberpunk joy – with a huge helping of agency, choice, combat, exploration and stealth on the side – and don't feel like waiting to see what fresh wackiness CDPR gets up to in a few years' time, take my advice and glance backwards.

I'm sure more great cyberpunk games will come along eventually but – until then – some of the best renditions of the future await us in the not-so-distant past...