It's hard work being Shepard...

You show up to a space prison, in good faith, thinking you're there to recruit an asset only to have the warden do a double-cross and try to put you in the slammer. So you fight your way free, cut a swathe through a bunch of guards, only to finally arrive at her cell. You set the thing to defrost, Grunt says something adorably dumb like "Jack is small" and you're still wondering how this will all pan out when little Jack tears free of her restraints and, with a roar, just keeps on tearing — through three massive robots and the space prison's bulkhead wall.

Following in her wake, hearing panicky damage reports from prison staff and seeing – first hand – the carnage she has wrought, you think to yourself "Suicide mission? More like cakewalk, from now on." With a power like Jack on tap, you might as well take up knitting 'cause there won't be a whole lot of fighting to do once she's in the mix...

And then, later, you take her out into combat for the first time and she leaps out of cover like an idiot and gets shot unconscious by some run of the mill grunt. You feel cheated – and rightly so – because, for the first time, you are meeting Gameplay Jack. And Gameplay Jack – unlike her powerhouse Cutscene Jack alter-ego – is, sadly, nothing to write home about.

When I was younger and computer games were still something of a budding enterprise (read: in the 1990s), I always looked forward to seeing a cutscene. In those days, what with the realm of 3D graphics limited to blocky vectors or Doom-like pixels, cutscenes were pretty much the only place where you could see fully-articulate, lifelike animation. They were a little window into the future, if you will, promising a degree of technology that was just then, sadly, still out of reach.

Nowadays, however, what with expansive environments, astounding special effects and motion-capture animation being part of regular gameplay, cutscenes seem more like a throwback: an admission, on the dev's part, that the game has arrived at a juncture they couldn't figure out how to handle and so transformed into a static, non-interactive showpiece that gets the player over the hump and back to playing the game.

Which is not to say that Cutscenes Shouldn't Exist or All Cutscenes Are Created Equal, but – increasingly – excessive use of cutscenes, QTEs or railroading is starting to look more like the symptom of poor planning than a viable design decision.

A matter of nomenclature

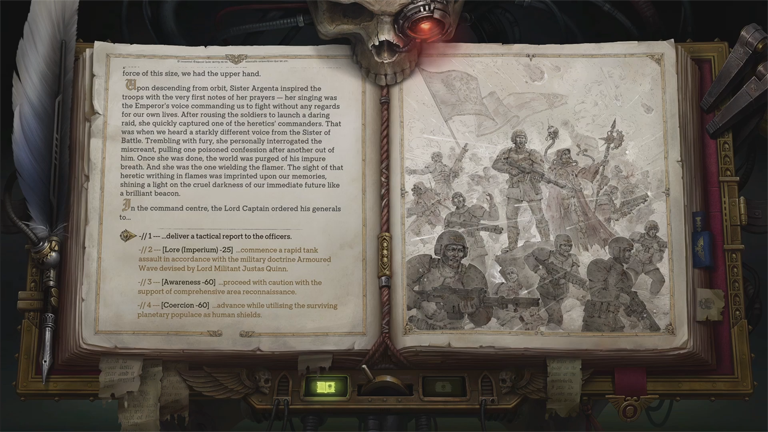

When I say "cutscene", I don't necessarily mean "movie-like 3D production with fluid animation, lighting and effects." Those Rogue Trader text sections that move the action away from the game's Unity engine and onto a page with written paragraphs and multiple choices? That's a cutscene. So is a QTE section in Tomb Raider, where you're pressing certain buttons so that poor Lara doesn't get impaled, stabbed or crushed, or whatever, the poor girl. Or having Cyberpunk 2077 take the reins and seat V in Dexter DeShawn's car to wax poetic on lifestyle alternatives...

Broadly speaking, a cutscene (in my mind) is any contrivance that moves the game out of regular gameplay to cover for the fact that it could not be resolved by the capabilities of the game's engine.

Sometimes, especially in Games of a Certain Budget, a cutscene is the right move. When you're toeing the line on funds but want to stay true to a grander vision than you can probably afford? That's when a cutscene is understandable. You wanted a flying opponent and a madcap dash through Commorragh's claustrophobic back alleys, but all your engine is built for is XCOM-like walking and shooting... I get it. That's a suspension of disbelief I can get on board with.

But if you're CDPR and you spent eight years building your own, hella-impressive engine only to deliver a game whose every crucial moment is relegated to railroading, cutscenes or QTEs? That, my friends, is Poor Planning At Its Finest and – what's worse – not only doesn't cover the oversight, but also leads to a gameplay experience that feels disingenuous — fractured as it is into two parts that don't fit together all that well.

Lucretia My Reflection

If it feels like I harp on Cyberpunk too much, it's only because I love it and play it a lot (to avoid admitting how much, I'll just say that an average V run takes me about a hundred hours, I'm currently on V four of seven and let you do the shameful, shameful math).

"Too much familiarity breeds contempt," a French (I'm guessing) bloke said in the 1340s, and while my overexposure to the game hasn't left me feeling contemptuous, exactly, I'll cop to the fact that running through it so many times has made its flaws all the more apparent.

The core of the problem is that Cyberpunk 2077 is not one cohesive whole but two clashing halves.

On the one trotter, it is a fantastic open world FPS+ that lets you go (almost) anywhere and do anything (within the confines of the FPS+ premise). In this mode, the player rightly feels like a driver: the person in control who determines what course the gameplay takes and how (adjusted for ability) it will be resolved. It's an empowering, fun experience to be able to go in any direction you fancy, tackle tasks in whatever order you see fit and chart your own course to their completion.

Not so Cyberpunk's other half, which takes the wheel away from you and downright tells you what's gonna happen, like it or not.

Hot on the heels of the ultimate freedom, these cutscene/QTE/rairoaded sections feel about as good as taking an airbag to the face. Every time V walks into that fist right after Dex pretty much spells out the impending double-cross doesn't just feel bad or emasculating – it feels insulting. I mean, first the game establishes the player is capable enough to handle a hotel-full of Arasaka's finest and then yanks the carpet out from underneath by having V succumb to a single, heavily telegraphed punch from some third-rate heavy. Not only that, but the entire episode is completely out of the player's hands — a pre-determined outcome, as it were... That, in a word, is cheap.

And when this occurence is not an isolated incindent but a recurring trend, well, it can't help but grate against any goodwill generated by the other (better) half of the game.

Best foot forward

Want to know how that bathroom sucker-punch situation could have been handled better? Look no further than good old Deus Ex. In that older – in some ways more thoughtful – game, there comes a point where you have to go see your brother in a hotel. People are after him and, after some dialogue, he tells you to hotfoot it outta there so you don't get caught as well. And you can. But the cool thing is — you don't have to...

If you do run, you find out later that Paul was captured and taken to a secret facility. If you choose to stay and fight (and win), on the other hoof, you both make it out of the hotel but – later – you are captured and taken to the facility anyway.

Now, Deus Ex was a lot smaller and less complex than Cyberpunk (38 hours, all told, where the later game can easily stretch beyond 124); and its branchings were limited (regardless of what you do in the hotel, Paul ends up captured in the end); but the difference was in its approach. Deus Ex framed its story in a way that allowed the player to keep driving – to make decisions and actually play, even if the results had to be stacked a certain way for the plot to continue. The game had a narrower scope and more constrained level design but at no point did it dangle a carrot in front of the player only to whack 'em across the fingers with a stick.

Cyberpunk 2077, on the other hand, is flawed right down at the basic design level. On the one trotter, it boasts unparalleled freedom but – on the other – it has no mechanics in place to guide said freedom: when it comes time to move the plot along, the game just steps in and takes over without any input from the player... And the regrettable thing is – it didn't have to be that way.

If, when you left that fateful No Tell Motel bathroom, the game simply presented you with two opponents instead of the "lights out" cutscene – or even a sort of Body-based, Renegade-interrupt (pass if your Body stat is high enough) – the outcome of the encounter wouldn't have to diverge much from the plot (no change if you fail to beat Dex and Oleg, or Takemura tracks you down someplace else if you win); but would have felt like playing instead of spectating, which – at the end of the day – is the whole reason games are a thing.

Extrapolated to the immense scale of Cyberpunk, implementing this kind of approach in every questline would be more work (which is why so many cutscenes permeate the experience); but – ultimately – it would have also made for a more cohesive experience where you don't spend half the time freewheeling and the other being led by the hand like a willful child.

March of progress

Like most development hiccups, an overreliance on cutscenes is either a planning or a communications problem. Planning, if everyone's on the same page but gameplay segments the engine can't handle are included anyway; and communications if the folks constructing the narrative aren't made aware of what's doable and what isn't. With a bit of forethought, both seem like wholly manageable issues

If gaming is to continue to evolve, so too must the underlying technology and while, in the past, concepts existed that were beyond what could be rendered, I think we passed that milestone many years ago. Hopefully, in future titles, we'll start seeing even more player agency and solutions to situations that depend on gameplay and skill, rather than some impromptu, QTE deus ex machina...

Maybe then, it will be possible to dodge a gimmicky punch, choose not to dive into white water littered with sharp, Lara-impeding things, or even wade into battle with knitting needle, yarn and utter peace of mind guaranteed by the fact that, just a few steps ahead, walks an actual biotic goddess...