Thinking back to the Wild West madhouse that was the heyday of the Amiga 500, there were a lot of studios I admired. Whether it was Cinemaware, with their impressive, movie-like graphics and intriguing premises ("Ants. Get 'em off! Get 'em off!"); The Bitmap Brothers, with their wholly unique style; the powerhouse that was Psygnosis, with its prodigious output; or even Core Design, whose wee homage to Indiana Jones (Rick Dangerous) would eventually evolve into the blockbuster franchise of Tomb Raider, the 1990s were rife with talented developers intent on leaving their mark on gaming history.

Talent aside, however, most studios specialized: they would find a groove that suited their capabilities and interests and produce games in that vein. To wit, Bullfrog loved their godhead, isometric strategies, Gremlin was enamored with racing, platforming or action and Westwood Associates lived and breathed RPGs...

But there was one studio that kept dodging labels, with nearly every game presenting a fresh outlook, a different genre, new mechanics or even a completely different engine. And that studio was Silmarils.

Founded in 1987 by the brothers Rocques (Louis-Marie and André) and named for the three jewels which shape the worlds of dwarves, elves and humans in J. R. R. Tolkien's Silmarillion, the studio was fond of subverting expectations and not getting tied down to a particular gaming methodology, with titles ranging from side-scrolling adventure games and puzzles to first-person RPGs and (I do believe) one of the first instances of the Dreaded Survival Genre...

While their most memorable games were Crystals of Arborea and the Ishar trilogy (which were open world, first-person RPGs similar to Eye of the Beholder), what I remember most fondly were their four adventure side-scrollers with an engine in common but — little else.

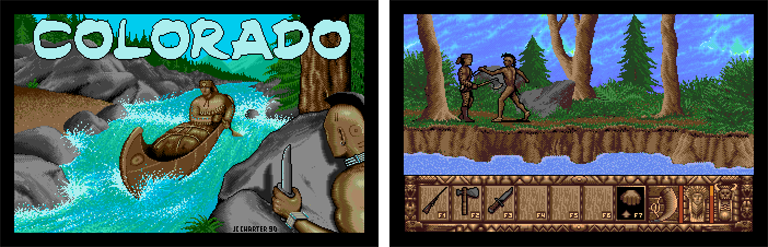

There was Le Fetiche Maya (1987), which – like Rick Dangerous – paid homage to the treasure hunter lifestyle and split action between side-scrolling walking, fighting and trading and first-person (kinda) driving. Colorado (1990), which put you into the well-worn moccasins of a James Bowie-like frontiersman type, who – armed with knife, tomahawk and rifle – traverses a mighty river using his canoe. Star Blade (also 1990), wherein you played a galactic explorer replete with his own starship, shuttle and even "laser sword" (read: lightsaber) that could freely travel between colorful alien worlds. And good old Metal Mutant (1991) that saw you control the walking trifecta of cyborg, dino and tank – a single character that could switch forms on the fly, each of which could be upgraded with new moves and abilities.

To be fair, the gameplay of these four titles was very similar (and composed largely of walking, jumping, climbing and fighting); but Silmarils' ability to differentiate them with unique settings and varied mechanics (such as trading in Le Fetiche Maya and Colorado, sandbox-like space travel in Star Blade or ability-dependent puzzles in Metal Mutant); and gorgeous visuals made their differences out-shine any inherent similarities.

On top of their unique design, each game also offered the ability to save the game (not a common feature, way back when); and included non-linear, sandbox-like gameplay and (with the exception of Metal Mutant) inventory management — emergent features that would not catch on as standard for years to come.

As a hilarious little palate-cleanser, Silmarils delved briefly (just for this one game) into the puzzle genre in 1991 with Boston Bomb Club – a top-down exercise in bomb disposal, wherein you guide tumbling, lit explosives to a water-filled bucket in the comfort of a private gentlemen's club.

Not that long (30 levels' worth, if memory serves) and not overly complex, the Bomb Club nonetheless had that unique mix of charm and playability that made it endearing even if it wasn't, in the strictest sense, great. While the gameplay was, essentially, that of Logical, the classier presentation and the fact the audience could bet on (or interfere with) the arrangement of the track made for a funnier, more soulful experience.

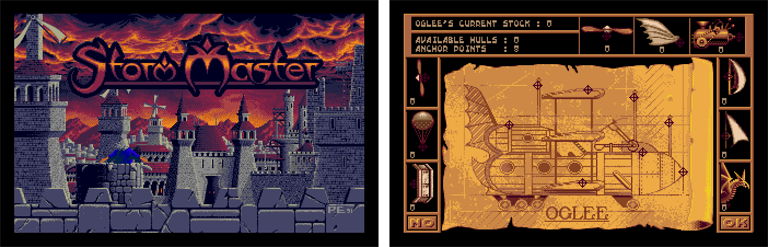

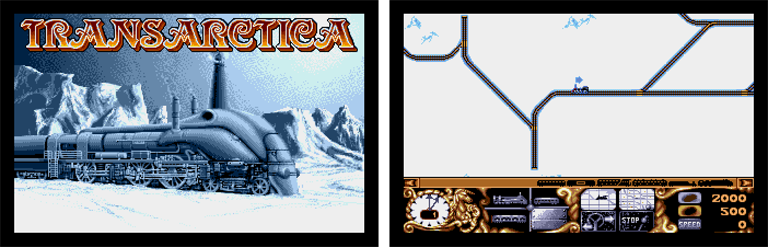

With action-adventure, RPG and puzzle credentials in the bag, Silmarils then decided to branch out into strategy a little, with Storm Master (1991) and hauntingly captivating Transarctica (1993).

In Storm Master, your conquest of a medieval world was accomplished through Da Vinci-like flying machines, which (for better or worse) you designed yourself (I still remember the tension of watching test flights which could – and often did – end with, shall we say, resounding results). The fantastical setting also let you spy on enemies via homing pigeons, balance your kingdom's budget and – naturally – wage war on your neighbors (whether on the world map or via kind-of-first-person air combat).

With varying wind conditions (which could sway the effectiveness of your vessels), a hint of diplomacy and even elemental magic, the game married distinct presentation with a lot of unique ideas for a truly memorable (if slightly awkward to play) experience.

Transarctica, on the other hand, was a kind of alternate-history Last Train Home, where you navigated a bleak, nuclear-winter wasteland with the aid of a fortress-train. Between maintaining and running the vehicle (accomplished via adorable, retro UI of actual stokers and ornate control panels); trading with isolated towns, buying new cars, random map events and frantic inter-wagon combat, the game offered much more interest than its sparse setting may imply.

Because of French practicality (and in keeping with the game's brutal setting), Transarctica also offered a convenient way to stop playing in the form of a loaded pistol in your quarters, should you run out of coal, blow a boiler or simply want to quit in the most drastic way imaginable...

To round out their catalogue, Silmarils finally delved into (or possibly began?) the survival genre with Robinson's Requiem and its sequel – Deus.

In both, you play Trepliev 1 – an explorer (and later bounty hunter) who crash-lands on an alien world and has to survive through scrounging and his own wits. With (for the time) steep system requirements, gameplay reviewers described as "dull" and a learning curve of "alpine" proportions, the games were not that user-friendly or enjoyable to play.

What they did accomplish, however, was introduce survival mechanics (such as managing hunger and thirst, self-diagnosis, damage that affected gameplay and even surgery); a unique system that let you combine items into (hopefully) more helpful variants; and gave rise to a whole new gaming genre (my least favorite, if we're being honest, but — still).

If you enjoy playing the likes of Frostpunk, Don't Starve, The Long Dark or Pacific Drive, know that you have Silmarils to thank for getting the ball rolling.

After 16 years and 24 games (which, toward the end, devolved into sad movie license adaptations), the studio declared bankruptcy and finally shut its doors in 2003 – the end result of their North American publisher (ReadySoft) being bought out, which prevented Silmarils from publishing their games overseas and significantly undercut their profits.

Personally, I think their greatest strength (the ability to make each release different and distinct) may have also ultimately worked against them. While specialization may seem more like a limitation than an asset, it's really the only way to excel at something – by doing it over and over again, with each iteration slightly more refined than the last.

It's the reason Bullfrog finally hit it big with Syndicate and Core Design enjoyed the immense success of Tomb Raider. Silmarils, on the other hand, made each game its own unique experience but – in doing so – never had the opportunity to meaningfully improve them.

Following the studio's closure, the Rocques brothers joined former Silmarils artist and designer Pascal Einsweiler and founded EverSim Games in 2004 and have since focused on "serious games" (which, according to their site, are "products (for) professionals (in) defense and security sectors for training and learning").

I'm happy some vestige of Silmarils lives on to this day, but – as I am neither a security consultant or that acquainted with geopolitics – I prefer to remember them as they were: a capable, keen little studio that could surprise and intrigue you with every new release.