Every storytelling medium has its essentials – fundamental components without which a narrative cannot unfold. Books need characters, movies require tantalizing visuals and the venerable radio drama of yore simply cannot function without atmospheric sound... But games are different. Unlike all other storytelling media, games can dispense with any (or all) of these components and still function — and it is in such sparsely populated depths that In Other Waters spins its yarn.

It's not elaborate, as stories go: you play the onboard AI of a diving suit (just go with it) donned by a Xenobiologist With Backstory (called Ellery Vas) who is looking for a colleague in the oceans of an alien world. This colleague – Minae Tomura – kinda wrecked Vas's career before taking off for parts unknown. Then, years later, she sent a plea for help from a distant planet that – by all accounts – shouldn't contain any forms of alien life (except it does). So Vas goes to the alien planet, dons a diving suit and sets off in search of his long lost colleague — except Plot Happens, he can't pilot the suit himself and has to depend on the onboard AI to chauffeur him around.

While the justification for the meld between plot and game mechanics is a little thin (Vas is perfectly capable of building propulsion systems from alien technology but can't operate a diving suit himself!?); it's not so hacnkneyed that it gets in the way of the narrative.

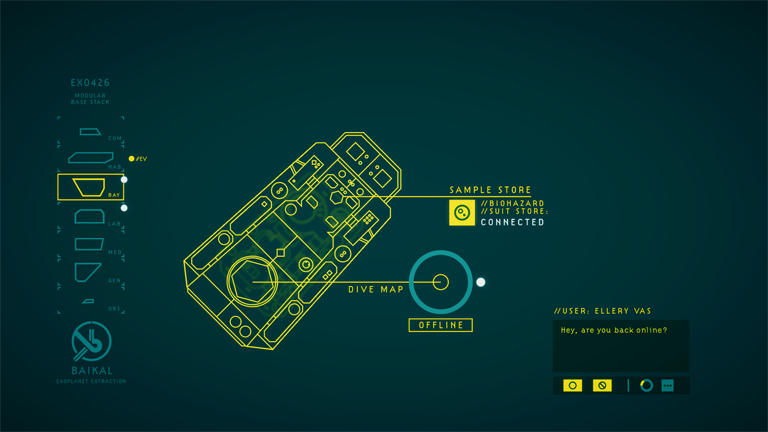

As the AI, you ping the suit's surroundings with sonar and then select which of the fixed nav points to travel to. As you traverse the topographic map of the ocean bed, you have to be mindful of the suit's power and oxygen (both deplete as you move). You can also pick up biological samples (which can be researched or used to replenish the suit's resources); interact with machine systems (such as computers or ROVs); and hail drones to ferry the suit between waystations (where you can resupply, research samples and listen to Vas unspool).

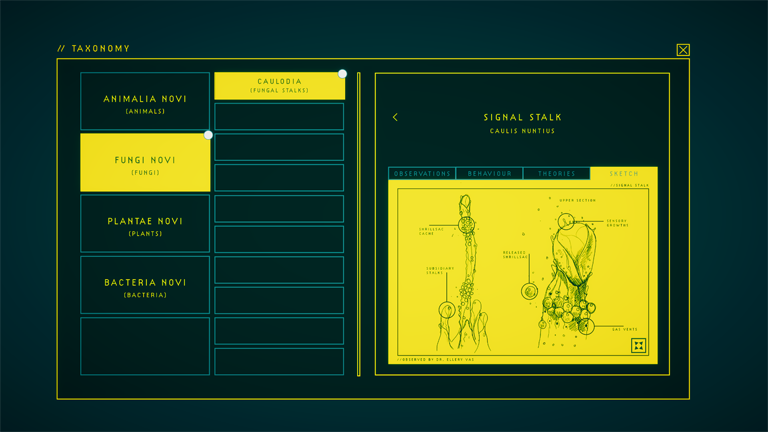

Short of the wee sketches of fully-researched fauna and flora, In Other Waters depends on simple vector drawings of the map and text for exposition – both adequate for the premise of an AI interpreting real world data. Plants and animals are shown as little yellow dots, diving is simulated via a darkening or lightening of the map and the UI's color scheme alters to reflect real world conditions (such as turning sickly green when the suit delves into toxic waters or going pitch black when depth exceeds a klick and a half). It's a tidy – if minimalistic – visual suite that fits the game's setting to a tee.

The narrative is compelling enough, with sufficient intrigue to pull you along, but very linear and entirely one-sided. As the AI, your only interactions with Vas are rare instances when – in the midst of a verbose monologue – he will ask you a question, to which you can only respond "yes" or "no." Hardly the basis for engaging dialogue and a bit prohibitive when it comes to player investment – which is where In Other Waters' greatest design flaw can be found.

By making the player the AI controlling Vas' diving suit – and not Vas himself – the game removes most reasons to care about anything that happens in it. Every motivator for the plot belongs to Vas: he cares for Tomura; he wants to find her; he is curious about the planet's alien life forms and ecosystem; he is the one who figures out how it all interacts, how to remove obstacles, where to go and what to do... It reduces the player's role to equal parts spectator and gofer – and given how sparse the game's visuals are and how clunky and repetitive the controls can be, neither is particularly rewarding.

Still, if you can look past these shortcomings, In Other Waters is a relaxing experience with a neat-enough story to tell that doesn't outstay its welcome (if you don't bother with the optional research runs, the game is only about 4 hours long).

More than anything, the game is a successful design exercise in minimalism proving once and for all that games do not require all the trappings of other storytelling media to function...

Unfortunately, what it also proves is that just because you can do without something doesn't necessarily mean you ought to.