Although the term "4X" did originate with a Master of Orion preview, examples of the genre predated it by about a decade — with (arguably) it's finest example ever published two years prior (a certain Civilization, by one Mr. Meier). But even though MOO was not the first, true 4X game, it established the formula for 4X games set in space that has remained largely unchanged to this day (and by "established the formula," I mean "came up with nifty mechanics later games shamelessly copied").

It's the reason why most modern 4X spacers – like Galactic Civilizations, Endless Space, Space Empires or even (gag) Stellaris – are instantly recognizable to anyone who has ever played MOO — with similar UI, carbon-copy concepts and mechanics that vary slightly (if at all). From a galaxy map, world management, diplomacy and research, to ship design, tactical space- and ground-combat, all of these games have "emulated" the ideas and gameplay set down by little old SimTex in 1993. But while MOO spawned many contenders in its wake, my all-time favorite 4X game set in space would always be a little closer to home.

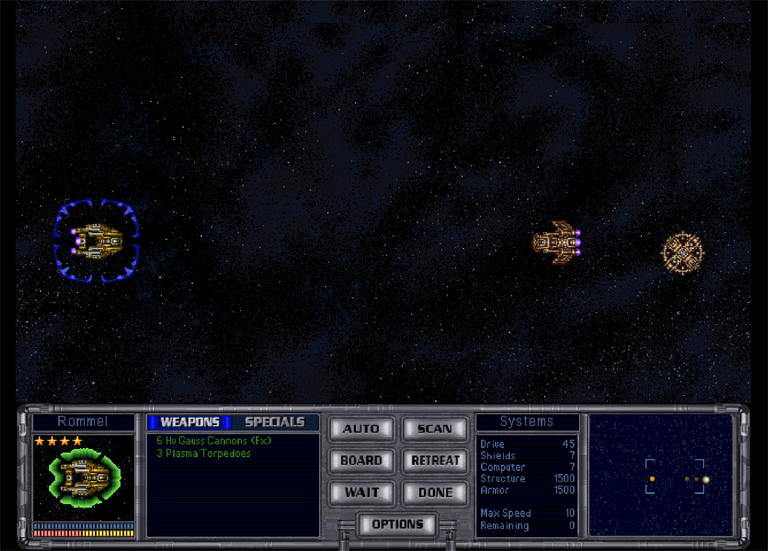

Made three years later, in 1996, by the same wee studio (which only ever released four games and existed for a scant nine years), Master of Orion II: Battle at Antares struck that unicorn balance of solid programming, great design, beautiful artwork and haunting music that could never be filed under any heading other than "classic."

The game's concept was simplicity itself: conquer the galaxy. But while the goal was straightforward, how you accomplished it was left entirely up to you.

Right from the outset, the game offered many ways to customize the gameplay and level of difficulty. You could control the size of the galaxy, its age (which determined the types of planets it would contain); the number of opponents, beginning level of technological advancement, whether you would direct combat or have it resolved automatically (for strategy purists and Humans Who Dislike Fun, I suppose); the presence of random events, overall difficulty and – lastly – whether the titular Antarans would appear periodically to pummel the snot out of you.

Eminently customizable, MOO2 allowed the player to mould it to their liking so that anyone – from a hardcore strategy devotee to the greenest noob that ever lived – could get the same level of enjoyment out of it. And – believe me: there was plenty of enjoyment to be had.

Once you established the terms of your sandbox, you picked which of the game's 13 distinct races you would lead to dominance and glory. Each race was designed with a certain play-style in mind, so that the burly Burlathi (larger than your average bear) made for the best ground troops and marines, while the Sakkra reproduced at an astounding rate but (as befitted giant, purple lizards) made for crap spies. Despite their advantages and handicaps, each race could still be played however you liked, but – obviously – would excel or underperform in accordance with their traits. Lastly, in true MOO2 fashion, if you didn't fancy being an ant, a cyborg or — whatever the Trilarians were supposed to be ("lunch", according to the Mrrshan) — you could always design your own race in the same perks-for-points system the others were based on.

While each MOO2 session started you out on a single world with one colony barge and two underwhelming scout ships, no two playthroughs were ever the same. The galaxy was generated randomly, so while – in one game – you may start on a rich, fertile world with plenty of colony prospects nearby, another might hand you a small, dry lump of dirt right next to an opponent or a space dragon lair, severely limiting your options (unless, of course, your custom race were space lemmings).

From those meager beginnings, you were left to expand, research new technologies, grow your fleet and triumph over opponents and frequent random events (which could see you richer by an anonymous donation, undercut by a sudden change of gravity on your most prosperous world or, indeed, ground to dust by a sudden Antaran invasion). But how you went about winning your MOO2 session was left entirely up to you.

For the warmongers among us, you could simply construct the most ships and pummel your enemies into oblivion (or subjugate their worlds and have them work for your cause). For the mercantile-inclined, you could form trade agreements and amass enough money to bribe your way out of trouble. For ninja-ilk, you could expand your, shall we say, intelligence gathering aparatus and wantonly steal technologies, sabotage factories or assassinate to your heart's content. And for reasonable normies, you could always let diplomacy lead the way, make alliances and simply Talk Things Out.

Or any combination of the above.

Not one to waste a single trick, each game of MOO2 also randomly placed Orion on the galaxy map. A veritable treasure trove, colonizing the planet rewarded you with many advanced technologies, which could give you the advantage you needed to triumph (not that getting to colonize Orion was all that easy, thanks to the presence of its overpowered Guardian).

A MOO2 session was won if 1) you were elected as the Supreme Leader of the Galaxy 2) you researched and built a dimensional portal, traveled to the Antaran homeworld and gave them what for; or 3) your race, for whatever reason, seemed to be the only one left standing.

In the 27 years (!?) since Master of Orion II was published, countless games have been made in its image. Some have refined its mechanics or introduced new gameplay elements and many may have upgraded their visuals into the realm of true art, but – in terms of coherence, polish and overall design – not a one has surpassed what Steve Barcia and SimTex set down as the Gold Standard nearly three decades ago.

If you enjoy 4X games, but have somehow (gasp!) never played or (double-gasp!!) never even heard of Master of Orion II, do yourself a kindness and give it a try. A bundle containing it and MOO-senior can be picked up on GoG for two bucks and change, which – somehow, for what you get in return – seems almost offensive. On my desktop, it's shortcut might seem out of place among later, more advanced games with bigger production budgets, but it has been there for 11 years for a reason...

...and it's not going anywhere.